- Home

- Sunil Yapa

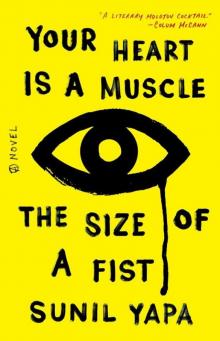

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist Page 2

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist Read online

Page 2

Their words had the quality of midnight prayer, deep from the depths of another sleepless night, as if the right words might call forth a future where they need march no more.

They said, “We’re going to shut those corporate motherfuckers down.”

John Henry heard their voices and knew this was no ordinary protest, this congregation in the streets. No, this was the new American religion. This desire which leapt continents. The longing of the heart to embrace a stranger and be unashamed.

They said, “A global nonviolent revolution.”

They said, “How beautiful and brave when a people rise for what is right.”

Six a.m. and he watched them swarming the streets of his city in a gauzy mausoleum light, a people’s army climbing from basement mattresses and garage apartments, the skyline of the city black-crowned and spooky at their back.

In their hooded sweatshirts and shin-high boots they looked like end-of-the-world penitents stretching into the dawn. Hip to the world’s saddest sins.

They said, “The future belongs to us.”

And maybe it did, but they looked so young, so young and fragile, and when the time came would they have courage—would they have the discipline to make it so?

Look with him at his people. This man who once preached from a pulpit, John Henry, who was wound up and weary with too much love, too much joy, too much rage. How many shelter cots that barely registered the man’s weight so light he was, the soft pillow of how many stone steps had cradled his head? John Henry, who had lost his church, look with him at his people. Look at his god made manifest in every form and shape of the broken world. Look with him at how they exit the church in an orderly fashion and tip their chins to the sky. Look at how they come from the darkness of their homes, backs stiff, stretching and tying the bandannas tight, checking one another’s faces for an idea of what violence this day might bring. Look with him at these wet American faces, ordinary and beautiful, and tell me you don’t feel more than a little bit afraid.

They wanted to tear down the borders, to make a leap into a kind of love that would be like living inside a new human skin, wanted to dream themselves into a life they did not yet know.

He heard them in the streets saying, “Another world is possible,” and beneath his ribs broken and healed and twice broken and healed and thrice broken and healed, he shuddered and thought, God help us. We are mad with hope. Here we come.

3

Officer Timothy Park knocked his riot stick against the stiff polycarbonate of his armored leg, producing a hefty sort of clack and whack, which, right this second, he found immensely satisfying as he sucked a black coffee spiked with fifteen sugars and watched the way they walked, heads high, arms swinging, and thought: Why in holy hell do these people look so happy?

Surely they knew they were going to lose?

Welders greeting plumbers with flung-open arms; scrawny old guys with crooked backs and the kind of crappy cardigan his dad used to wear while raking leaves, they were shaking hands with society ladies strung with pearls, and Park grimaced as they hugged and helloed, threw their arms around one another’s necks, a grainy mist falling. Hugging? Why were they hugging? The last time Park had hugged someone had been at a funeral.

Park was standing beside the department’s armored vehicle—affectionately known as the PeaceKeeper—with his sometime riding buddy, Julia. The PeaceKeeper was some civilian version of an armored Humvee—a great metal duck painted matte black with tiny rectangles for the driver’s windows like the slits in hilltop bunkers and down below four fat tires which meant they could roll wherever they pleased. There were two swinging doors on the back, a hatch to pop your head from the top, and running boards on each side, and look at Ju there kind of lazing around like it was a cover shoot on some tropical isle, one hand resting idly on the butt of her department-issue pepper spray, the other resting against the side of the vehicle where the letters were painted huge and white:

SEATTLE POLICE DEPARTMENT

Call her Miss July, even though it was, in fact, November and a probable riot situation. But Park didn’t mind the riot gear, didn’t mind watching Ju’s body absorb the rough vibration of the idling truck. Call her Miss November Riots if you wanted—she was as lovely as a parade rifle that the kids spin and twirl—and watching her was his reward for the frustration of having to police a protest march. Protecting an anarchist parade, that was the kind of world we had come to, but Ju was beautiful and tough and what was the word? Willowy? Park didn’t mind the show at all. She was like a video game knockout is what she was and ever since he’d moved to Seattle and joined the SPD he’d been trying to get her out for a drink. The guys in the precinct all laughed—everyone wanted to sleep with Ju; that Mayan, almost Asian look she had going with her bronze skin and dark almond-shaped eyes, that razor-sharp tongue that could cut you a new one in two languages, the long hair tucked high in a ponytail the color of coal-black tar. The thing Park liked was her eyes. He thought she had brown eyes so bright they could have been used as lights in some kind of emergency operating situation. If the need arose.

When Park told his buddy Baker about his crush, Baker looked at him crosswise. “That one?” he said. “She looks at you and you feel like a bug waiting for the shoe, but, you know, like, pleased about the situation.”

“Yeah, I know,” Park said, “but…”

“Like happy you’re gonna get squashed,” Baker said, laughing and walking to the vending machine. “Like you think it’s going to feel so good to get stomped.”

Park watched a group of young people taking over the intersection in front of him. They were a part of the crowd, and yet separate from it in a way he couldn’t define. One minute it seemed an undifferentiated mass, and then these young people materialized out of the chaos of bodies.

To his eye they were wearing stained and greasy jeans like some kind of junkie army risen from their mothers’ pullout couches, but there was an urgency to their movements, shuffling quickly like they were loonies five minutes escaped from the Harborview nuthouse on Ninth, and he sipped his coffee and laughed. There was a calm camaraderie, too, a sort of ease he recognized. As though they were an elite military unit—saying little, communicating instead out of seasoned memory, the easy gait of shared purpose.

He set his coffee on the ’Keeper and watched in total stunned astonishment as they sat down in a circle and then began locking themselves together with chains and PVC pipe.

Maybe as an officer of the law he should be doing something about that?

He turned to Julia and nodded toward the kids.

“I mean what’s going on here, Ju. Are they protesting the world?”

Julia—Ju—she looked at him in that way she had of looking at him. As if a thousand miles stood between her body and yours. Or so she wished. Aristocratic, was that the word?

“Are they protesting the world?” she said flatly. “That’s what you want to know?”

“Yeah.”

“Which one, Park?”

“Which one what?”

“Which world, pendejo? Yours or theirs?”

He turned away. The PeaceKeeper was parked in the zebra lines of the south crosswalk at Sixth and Union, its ass with the double doors pointing west toward a bank, its headlights and flat hood pointing toward a coffee shop, which was wisely, Park thought, closed and shuttered for the day. On the other side of the intersection, perpendicular to the wide side of the ’Keeper, beyond that mess of kids and hippies, a series of low wide steps fanned upward, creating a wedge-shaped plaza with the wooden benches at the bottom as the crust, which was funny, Park thought, because the plaza was not public, but private, narrowing and climbing as it approached the entrance, ending among potted ferns and the glass doors of the Sheraton lobby. Above the lobby, ivy-covered beige walls. Above that, gray glass rose a neck-craning thirty-five floors above the street. Pretty much your typical pretentious downtown bullcrap in the opinion of Park, who was feeling pretty irritated bec

ause he hadn’t eaten anything besides a banana and a power shake this morning and whose stomach was already growling despite that being only about two hours ago, when he woke at four a.m. to do abdominal crunches in the dust of the bare floor beside his bed.

A young mother in a thousand-dollar mountaineering jacket was circulating behind the PeaceKeeper. She was on the south side of Sixth, behind their lines, and Park saw her over the top of the PeaceKeeper distributing coffee and cupcakes from a tray. She seemed suburban and pleasant. Park noticed she had parked a baby stroller in the cedar chips of a municipal tree for which he could cite her if he chose, which he did not currently feel like doing, but as he reminded himself, he could if he wanted, which was the point. He stepped around the front of the PeaceKeeper and was pleased when Julia stepped down and followed him.

The lady approached them where they stood beside the PeaceKeeper.

She offered them the tray of fresh coffees and the paper-wrapped cupcakes, nodding toward the protesters chanting behind Park and Ju.

Her voice pitched conspiratorially, she said, “Aren’t they a pain? I mean, gosh, I thought the sixties were over.” She released a bright laugh as if a little surprised at her own naughtiness.

“All those banners and shouting,” the lady said. “What are they doing? It’s almost Christmas!”

She was sort of whining now and Park, his back to the ’Keeper, asked her to please step away from the vehicle. The lady continued forward as if she hadn’t heard, offering the tray to them as if she were in her living room entertaining guests.

Park put on his gloves and flexed his fingers until the fit was tight.

“I just don’t know what they hope to accomplish sitting in the street like that,” she said.

“I asked you to step away from the vehicle,” Park said. And then he paused and added, “What’s the matter with you?”

The woman smiled in a neighborly way as if these were just morning pleasantries, as if a smile were enough because, after all, they were on the same side—the cops and a friendly patriotic young mother offering coffees—they were on the same side here, right?

“I just don’t know what they hope to accomplish,” she said again, a little less brightly.

And just like that, Park’s baton was in the air and quivering just above the tray of coffees, pointing to her throat.

The smile plastered to the lady’s face like a light someone forgot to turn off.

“Park,” Ju said.

Some of the other cops had stopped what they were doing and were watching good-naturedly even as they unwrapped the lady’s cupcakes and gnawed at the edges.

Ju stepped in front of him. Normally he would never have allowed another officer to intercede in his arrest, his encounter. But Christ, it was Ju. She placed her hand on the baton. He lowered it gently to his side.

Ju looked him in the face. The acknowledgment passing there. There would be other, better moments. He nodded, said to the woman, “Thank you for the coffee.” Then, gesturing with his chin at the stroller, he said, “But why don’t you get your kid out of here? You know?”

The woman’s smile hadn’t faltered. Her eyes had gone wide, face pink as a plastic doll, and still she went on smiling like a thousand-kilowatt idiot in her mountain-climbing jacket and her stroller parked next to a goddamn armored police vehicle.

She stumbled backward away from Ju, away from Park. The tray crashed to the ground. Cupcakes and coffee spilled across the concrete steps and a general groan of misfortune went up from the assembled troops.

Didn’t matter. The lady was already halfway down the street, stroller smooth and gliding before her.

The cops returned to their conversations.

Park racked his baton. “Ju,” he said.

“What?”

“Don’t ever freaking do that again.”

“Chief said we should take it easy, Park. Chief said they’re nonviolent.”

“Nonviolent. Is that right?”

“Yes.”

Surgical, that was the word. Her eyes looked bright enough to be surgeon’s tools and Park sometimes liked to dream himself under the knife.

“Well, not for nothing, Julia,” he said, “but what does the Chief know? The Chief is as soft as butter on a picnic plate.”

4

Reports were coming in from all over the downtown, crackling through the radio clipped to his belt, and Chief Bishop knew he should be paying attention, but he felt distracted, a kind of tectonic drift of soul, as if something fundamental were loose inside, an oceanic plate going molten beneath the continent’s weight.

Tom-four-two.

This is Command. Go ahead.

Approximately seven thousand southbound. We see chanting and signs. Over.

Bishop listening to the radio chatter on his belt and looking over the growing crowd from a spot twenty feet above their heads in a cherry picker requisitioned from Seattle City Light. He felt a fondness for these people, a kind of love-struck nostalgia for his city. Americans marching in the rain. Their faces, failed and flawed—they were the faces of a part of American life that was passing away, if not already gone, the belief that the world could be changed by marching in the streets. Bishop perched like a bird on a wire watching the crowd from the cherry picker. He extended the crane to get above the bare branches of November trees, thinking he had protected these people for thirty years—first as a beat cop, and then as a captain going to the community meetings twice a week, which was where not incidentally he had met his wife, on and on up through the ranks, working the job, investing himself, practicing the profession of policing as he best knew, and now here he was their Chief, their leader—and, now, why now did they see the need to come marching like lambs to the slaughter?

Four-one-three to Command.

Go ahead, Four-one-three.

Anarchist seen headed south.

Can you describe the anarchist?

Black hooded youth. Over.

Bishop in the bucket at the end of a crane wearing his Chief’s blues with the five stars on the lapel. He kept himself fit, but he wasn’t a gym rat. He preferred to be outside—fishing, camping, diving—and after a summer spent diving alone in Mexico, hiking alone in the Cascades, he had a deep tan, a healthy glow about him that had absolutely nothing to do with his mental state or inner condition of the soul. His hair was sandy brown, going gray at the temples, his eyes a watery blue behind his out-of-fashion overly large glasses, and he held a radio in one hand and a megaphone in the other. He brought the megaphone to his mouth and clicked it on:

HEY YOU. YOU CAN’T PEE THERE. YES YOU. MOVE IT.

Bishop knew his son was out there somewhere in the ragged crowd. His sweet skinny ebony son, missing since August 1996. Three years. His son who had graduated from high school at age sixteen, part of an accelerated program where they jumped you grades because of your high IQ, and when you finished early you jumped your home because of your asshole dad. Or so Bishop supposed. Who knew.

His son left when he was just sixteen, disappeared into the world, and some part of Bishop’s memory still insisted on remembering him as that skinny sixteen-year-old sitting on his bed with his Jordan posters hanging on the walls.

“Electricity,” his son said, gesturing around his room, books stacked in piles on every available surface. “Do you ever think about what electricity means?”

And Bishop, thumbing idly through the odd titles, said, “Sure I do, son.”

“I flip the switch and the lights come on.”

“Son, go to college,” Bishop said, putting the book down. “We can afford it. Join a group. Hand out flyers.”

“I flip the switch and the lights go off. Where does it all come from?”

Bishop and Suzanne’s only son. Suzanne’s son, in fact, whom Bishop had inherited when they married eight years ago, so, not his son by biology or birth, but did that make the loss, the crush of longing, any less dense? He felt like he was sixty meters below and falling still.

“Go to classes,” Bishop said. “Meet a girl.”

His son—missing since August 1996, a little less than a year after Suzanne’s death—saying, “Water. I twist the handle and it comes streaming out. No buckets, no pails, no trudging to the well in the ashy light of dawn. Anytime I want it…boom! There it is.”

And Bishop saying, “The ashy what? Listen, college is the key. We can afford it.”

“Water in the kitchen. Water in the bathroom. Water in the garden hose.”

“Go to college. Meet a girl. Get a job.”

“Dad, are you even listening to me? Water. I twist a gold handle and it comes leaping out as if it had spent its whole life waiting for my sweet touch.”

Bishop paused. He saw them there in his mind’s eye, two men, blue-eyed father and brown-eyed son, breathing and talking in the son’s room, and him so blind, so alive and blind to the intensity of his son, of what it meant to live as a brown man, a black man. And which was his son, he didn’t entirely know. They had never really talked about it, one among a million things, and why should we, he is my son and I am his father and he, a black man or brown man, but a young man and me, his father, a grown man, and I love my boy. Me, a man who only wanted somehow to protect this younger, more vulnerable version of himself. Tell me what else is there to it?

“Son,” Bishop said, “suffering is everywhere. I see it every day. And if you wear your heart on your sleeve, the world will just kill you cold.”

“What’s that mean?”

“Stop caring so goddamn much.”

And if you were counting, Bishop thought, go ahead and add this conversation, which occurred one blistering summer afternoon exactly two weeks before his son took off, to the long list of his failings as a flawed human being, his failure as a father. Because, truthfully, Bishop had recognized the thing in his adopted son for what it really was—the fever of grief. It was a brokenhearted rage that he, too, felt slamming around his chest. Suzanne. Yes, the boy missed his mother and what did Bishop want to say? He wanted to say, Life’s a cruel thing, son. Give it enough time and it will take back everything you have ever loved.

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist