- Home

- Sunil Yapa

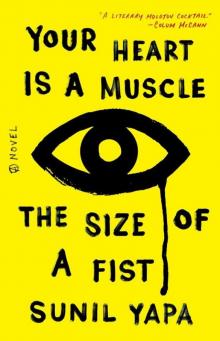

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist Page 3

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist Read online

Page 3

Three years his son had been gone. Suzanne—it seemed she had left just yesterday.

Four-one-three to Command.

Go ahead, Four-one-three.

We are a soft platoon here, Command. Permission to go hats and bats?

The Chief brought the megaphone to his mouth and then lowered it. What had he missed in the world that had brought these people into the streets? He watched them pass and felt a dip in his mood, the familiar phlegmy despair, because what kind of revolutionaries were these? They didn’t wire themselves with explosives, strap ball bearings and nails to their ribs. They didn’t detonate themselves in a crowded marketplace at noon.

No.

These were children who put their bodies in the street, who chained their bodies together and waited for the cops to come—his cops with their batons and their tear gas and their pepper spray.

Eighth and Seneca we see—

Three-five-one to Command. Over.

Bottle in a brown paper bag. Be advised.

He had scheduled nine hundred on-duty officers. Now they were looking at upward of fifty thousand protesters in the street and four hundred delegates—four hundred delegates from one hundred and thirty five countries who may or may not speak English—to safely shepherd from the Sheraton Hotel to their meetings at the convention center.

Nine hundred on-duty cops. Fifty thousand demonstrators, maybe more. It was only three blocks up Sixth Ave, and yet these streets were impassable. They might as well have built a wall in the intersection. He would have to clear the whole damn thing to get those delegates through to the other side. And how the hell was he going to do that? These streets were shut down.

Bishop watching the crowd, watching his line of officers and thinking about his son, when a voice cut through the noise. It sounded irritated, harried, on the verge of out of control.

Bishop, this is MACC, do you copy?

Chief Bishop recognized the voice as belonging to the Mayor and he imagined the Mayor there at the Multi-Agency Command Center, surrounded by FBI, by State Patrol, Secret Service, by all the agency men. The Mayor in a suit, talking tough and waving a cigar. Even though, to Bishop’s knowledge, the man did not smoke.

Anarchist seen headed south with flammable accelerant. Advise. Over.

Please stay off the

Is Bishop. Repeat.

Not under control. We need

This is MACC. Bishop, what is your situation? Over.

Repeat Bishop, what is your situation at the Sheraton?

The MACC was the new two-story complex halfway up the hill, the nerve center and brain trust for the officers in the street. The central control room was lined with monitors relaying information back from the more than two hundred cameras installed all over the city and where Bishop himself, as chief of police, probably should have been, but he wanted to be out here in the street. Where police belonged.

Bishop brought his radio to his mouth. What the hell was the Mayor doing at the MACC? He wasn’t a tactical director. He was a politician. A fucking PR man with wingtips and a firm handshake.

Mr. Mayor, sir. Our situation at the Sheraton is stable. I am seeing three to four thousand protesters in our area. But they are peaceful. Repeat they are peaceful. Over.

Bishop, the delegates. They need to be at the convention center. Where are the delegates? I got Secret Service breathing—

Bishop keyed his radio.

Mr. Mayor, the delegates are safe. I have instructed them to stay inside the hotel.

Sixth and Seneca. Over.

Please stay off the command.

Bishop, I need that street clear for the opening ceremonies. We need to get the delegates to the convention center. Do you copy?

Seattle Command, this is Three-five-one. 11-40 at Eighth and Seneca.

Bishop’s radio hung in front of his mouth like a forgotten forkful of supper. 11-40. That was a request for an ambulance. And then the Mayor’s voice was so clear a shiver went spilling dark and cold down the Chief’s spine.

Bishop.

Sir?

I don’t care what you do to get it done.

Sir?

Bishop, clear that fucking street.

5

Victor marched and moved with the crush, nodding his head to the syncopated beat. He checked out the hippie chicks in rain-soaked fairy wings, the punk chicks with pierced lips, and he laughed and did a sort of high-necked slouch strutting and bouncing down the street. His jeans were belted around his skinny waist and the extra loop of leather wagged loose from the buckle like a tongue.

He was high as shit.

For three years he had wandered the world and he remembered seeing burning cars on the streets of Managua; he remembered a man in India who would not eat; he remembered a line of women in their bowler hats and long skirts standing atop a hill on the high border between Bolivia and Peru, each with a stone in their hand silently waiting for the police. Protest. Globalization. Victor carried the two lines deep within him. He saw the secret and not-so-secret threads that connected his body in the here and now to worlds three continents away.

The dark sky above him like the dark sky above Shanghai where he had hardly seen the sun, people walking with surgical masks as if that would protect them from the fleets of particulate matter flying their skies like endless flocks of blackbirds bound for the rich nations of the West.

Victor pierced by clues and impressions gathered from the wind like pollen. It was like a radio dial between stations, the way they chanted and cried. The overlapping voices like whispers of other realms—come in, London, come in, New York, come in, Paris, France. Yes? Give China back her sun.

Doing the strut past Banana Republic, past Old Navy and the Gap. Beneath Niketown he stopped. The lights were on and people were in the stores doing their holiday shopping. People were drifting leisurely through the aisles, comparing prices. What were they doing behind that glass? Buying pants? He hammered against the window with a closed fist. A woman who was placing folded garments in a bag looked at him with a face like murder.

Whatever.

Trying to sell to a union man—that had been stupid.

He was smarter than that.

Since then Victor had made three more attempts. He tried a girl in a sundress who, when he offered, looked at him like he was diseased.

He tried an old man banging a goatskin drum. The old man closed his eyes, hands going full tilt, lost in the rhythm of his own making, and the way he smiled Victor figured he was already stoned.

He tried a kid in black boots and suspenders wearing a Rage Against the Machine shirt. The kid showed him a large X razored into the back of his hand. Victor had said, “Okay, but what about the weed,” and the kid just shook his head and told him to go fuck himself, he was straight-edge. Victor almost threw the weed at him, bounced it off his ugly fucking mug, but then he thought better of it and moved off, shaking his head, sliding the weed back into his zippered pack.

If only someone would buy a goddamn bag. At least an eighth.

People were looking at him funny, and he knew why. The pair of loose-tongued Nikes. Yeah, white Nikes with a red silhouette of a black man who could fly. Go ahead and look. He wanted that, he needed that, the edge, the distance, the fuck you. Wearing a pair of sweatshop shoes to a sweatshop protest—well, he wanted to say, what the fuck do you think you’re wearing? I wear my Nikes and they remind me I am small and the world is large and who are you to judge me for a thing like that? The world is large and I am small. The first thing he thought when he woke up. The thing he had thought at her grave just two days ago. Four years to the date. The last thing he thought every night when he went to bed in his tent with the waves bellowing and the cars chugging like ships passing through the port, every night since he had returned to Seattle three months ago, returned to his father’s house on the hill, busted the latch he had always busted, crawled in the basement window he had always crawled into (or out of), and retrieved the shoes in their box from t

he closet of his room.

So hell yeah, go ahead and look, people. They’re my lucky sneaks.

And then he saw them. The perfect boomer couple. Victor decided to go for the woman, she was wearing gold earrings in some Native design, attractive and kind of hip-looking in a funky hat. She was with her husband and a little girl who was stuffing carrots in her mouth.

Victor sidled up and went into a monologue, improvised on the spot, about marching for Native rights.

The woman’s eyes lit up. She began nodding enthusiastically, wisps of brown hair lifting in the breeze. “We’re marching with the Nature Conservancy,” she announced, something mildly apologetic in her voice. “Working on the turtles.”

“Freedom riders in ’64,” the husband said.

“Wow,” Victor said, “far-out.”

The note of pride in the guy’s voice contained something Victor suspected he was supposed to relate to, being a brown man with two thick braids, but he couldn’t guess what.

“Listen,” Victor said, trying to read their faces, feeling this might be his last and only shot at making some cash.

“You guys are some pretty cool heads,” he said. “Should I call you Mary Jane?”

Blank looks all around. He searched desperately for the perfect word.

“Reefer. Do you guys puff the reefer?”

“Wait a second,” the man said. “What are you trying to do?”

“Grass? Dope?”

“Are you trying to—?”

“Skunk? Dank? Pack a pipe of the kind bud?”

“Are you trying to sell me marijuana?” the man said.

Victor smiling huge, clapped once, glad they could finally connect. “That’s right,” he said. “That’s it, exactly.”

“Jesus Christ,” the man said.

The lady picked up her little girl and put her on her hip like a sack of groceries.

The husband was suddenly not so friendly. He was irate. Righteous-looking. “They put stoned Indians in jail is where they put you,” he said. “You know that?”

“Yeah, yeah,” Victor said, “I read something about that once.” He back-stepped into the heat of the crowd, looking at the little girl still shoveling carrot sticks into her mouth like trees into a mill. He wanted to tell her: Don’t grow up. Nothing but assholes.

They were mad and happy and Victor, he felt suddenly tired. Flat-out exhausted. He climbed a bench and sat with his feet on the seat, letting the people flow around him, feeling low, the self-pity and bile building in his throat. Fucking protest march.

Was that what you called this shit anyway?

A protest march?

When you take to the street to chant the chants, to stomp your feet and rhyme the rhymes?

And all the energy you spend, all the outrage and disgust, is not for you, no, not some sort of personal draining of the pus-filled guilt, but an expression of your compassion for a sad desperate people in a country far away?

Some expression of your compassion for that war-torn country whose citizens are just skin and bones, and who, you imagine, weep long into the night cursing God for a scrap of bread?

A protest march—that’s what we call this, right?

Or maybe they’re crying because their children make T-shirts in an export-zone sweatshop and yesterday there was an accident—the place burned to the ground and no one had the technology on hand to identify one pile of human ash from another.

Or maybe their son was shot in the head and dumped in a muddy hole and floured with lime and buried beneath a shallow mound of bulldozed earth.

Maybe it was HIV and they couldn’t afford the drugs.

Wasn’t that what it was called? When you called some friends and made a sign with colored paper and scissors and glue to express your solidarity with the charred bodies of children?

A protest march?

“Sometimes,” Victor said to nobody in particular, “I feel like I’m living on the fucking moon.”

“I know. I mean that’s why we’re here, right?”

He turned to find a girl sitting next to him.

She took his hand nonchalantly as if they were brother and sister, Christmas morning, circa 1989, waiting for the orgy of paper and presents. “Can’t you feel it? All these people out here together, marching for, you know, justice?”

Victor nodded. He was sort of noticing her hair. Noticing the way she was sitting next to him on the bench. She was pretty in a sophomore year of college kind of way with a button nose and a pink bandanna knotted peasant-style in her corn-silk hair.

She noticed him noticing.

“Don’t you have one?”

She touched her hair. Apparently she thought he was checking out her bandanna. When he didn’t say anything, she undid the knot. She unwound the bandanna, shook her hair free, and offered it to him.

“That’s all right,” he said, and touched his forehead where his own bandanna held back his braids. She smiled and shrugged and together they sat and watched the crowd.

On an impulse, just the good feeling of it, he leaned into her ear.

“Let’s get high.”

Victor felt an immediate ice. She was still sitting there, but it was a certain thing you could sense, a withdrawing into the self as if a switch had been flipped.

“It’s good shit,” he said, and reached for the half a joint in the pocket of his down jacket.

She actually stepped off the bench.

He bent and lit the roach. Made his body a cave in which a match could flame, and by god it did. He nearly cheered. He shook the match and took a great gasping drag. He held it in his lungs a beat, and then exhaled sweet smoke that zipped across the heads of the crowd like a little runaway train careening off a bridge.

The girl was just standing there looking at him. People were passing in the carnival behind her.

“You can’t do that here,” she said.

He offered it to her. “Don’t worry about the cops,” he said.

“No. Look, you don’t understand. This is a drug-free area.”

He took another drag and laughed smoke. “This is a protest march.”

“Where’d you hear that?” she said. “This isn’t a protest march. This is a direct action.”

“Whatever,” he said. He hit the roach again. “What’s the difference?”

She stepped forward, put one foot onto the bench, plucked the joint from his lips, and then flicked it to the ground and crushed it into the pavement with her boot.

“Fucking seriously, dude.”

In the beam of that cool knowingness he suddenly felt less sure of himself. How could he ever have mistaken her for nothing more than a sexy undergrad? She was a radical, a revolutionary, and he suddenly wanted to be as far away from her as humanly possible.

Her bandanna. The pink flap of cotton which had been holding back her hair. She pressed it into his hand and closed his fist around it.

“Trust me,” she said, beginning to move off, “you’ll want it later.”

Victor, frozen to the bench, dumbfounded, watched her go, the bodies moving past him, sat there mute and scared, letting the noise wash over him in waves.

He wanted to call out to her. He wanted to apologize, to throw away his weed forever and call her back.

He looked at the pink bandanna in his hand. He wanted to call out, “I’ll need it for what later?”

Which is when he heard the man’s voice. The pissed-off Freedom Rider husband saying loudly, “That’s him, Officer. That’s him, right there.”

Victor turned. The husband was talking to a cop on a horse. The cop was sitting tall. Following the husband’s finger pointing Victor’s way. There was something wrong with his face. A seriously nasty burn running along the right side of his jaw. And the look on the cop’s messed-up face? God bless him if he didn’t look like he’d just won the lottery.

6

Her name was Kingfisher, but her friends just called her King. She liked King, the small bite of irony, this tw

enty-seven-year-old white woman with dreads to the small of her back. She was tall, olive-skinned, vaguely Mediterranean if Mediterranean meant you were trash from coal mining country who could catch a tan easy. Her mother, when drinking, claimed some Cherokee blood way back in their family tree and that was just fine with King. She was muscled, thin, and tough. This woman with ambiguously light brown skin, with green eyes as bright as any sea, who at one time ran a sort of illegal animal shelter behind her off-the-grid house on an unnamed island beyond the city, who journeyed here with four friends in an Econoline van, the four of them eating sandwiches of sprouts and beans, this pretty girl in laced black boots who wore black jeans and a loose white shirt, the sleeves rolled to the shoulder like some kind of back-alley tough—she had the kindest of smiles, a smile which creased her mouth and lit those green eyes and which you could see were she not currently wearing a full-face black gas mask.

She turned to her friends and motioned them into the intersection, looking totally comfortable, a military person of some kind in her gas mask and jeans tucked into her boots, dreads bound with a loop of twine.

Her friends came running around the corner, heading for the intersection.

The police were standing on the southern side of the intersection, between a Niketown and a bank. King noted with amusement that the cops were on the wrong side. Like always. They were standing with their backs to the sloping streets, the streets dropping away behind them five blocks to the water. The convention center where the meetings were to be held was on the uphill side of the intersection, two blocks up Union, behind her, where her friends were now setting up their barricades in front of the Sheraton Hotel.

Look at them there. The line of cops in their riot gear. Standing still as statues thirty feet away while behind her, the crowd danced and sang. Here in the front they were calm, a row of seated protesters three souls deep, their arms linked at the elbow. The cops’ front line was calm, too. A solid wall of storm trooper flesh and King thought that said it all. They were humans after all, doing a job, and the need to move, the need to shuffle and shift in their heavy gear, was innate. But there they were standing still, not moving a muscle, staring straight ahead like they were those red-coated guards at Buckingham Palace.

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist

Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist